FIELD NOTES 2023

4.20.2023 Heaton Flats, san gabriel mountains

Heaton Flats Trail is a scenic trek in Southern California's San Gabriel Mountains. The trail extends around 8 miles round trip and gains about 2,000 feet in elevation, making it a moderately strenuous hike for those with some hiking experience. It starts from the Heaton Flats Campground, which provides ample parking and facilities for hikers. Consider turning around at about 3 miles near the ridge crest for less of a workout. An Adventure Pass is required to park; they are available at the ranger's station.

One of the key highlights of this trail is the breathtaking view of the San Gabriel River East Fork. The river sparkles with gold prospecting history, and hikers may often come across people panning for gold along its banks.

As you navigate the trail, you'll see a stunning display of Southern Californian nature. It weaves through a blend of chaparral and riparian landscapes, and the terrain varies from well-maintained footpaths to more rugged sections requiring a bit of scrambling over rocks.

The hike is mostly under the cover of canyon walls, keeping it relatively cool even during the summer months. Rattlesnakes are a constant presence in the mountains and it is important to watch where you step, especially off the trail.

Towards the end of the trail, you'll reach the impressive "Iron Mountain", often referred to as one of the most difficult hikes in Southern California. Here, you have the choice to turn back or continue on to this more challenging trail if you feel up to it.

The Heaton Flats Trail offers an abundance of wildlife spotting opportunities, including sightings of bighorn sheep, deer, and various bird species. It's also home to various plant species, making it a popular choice for botanists and nature enthusiasts.

The plant list is coming soon.

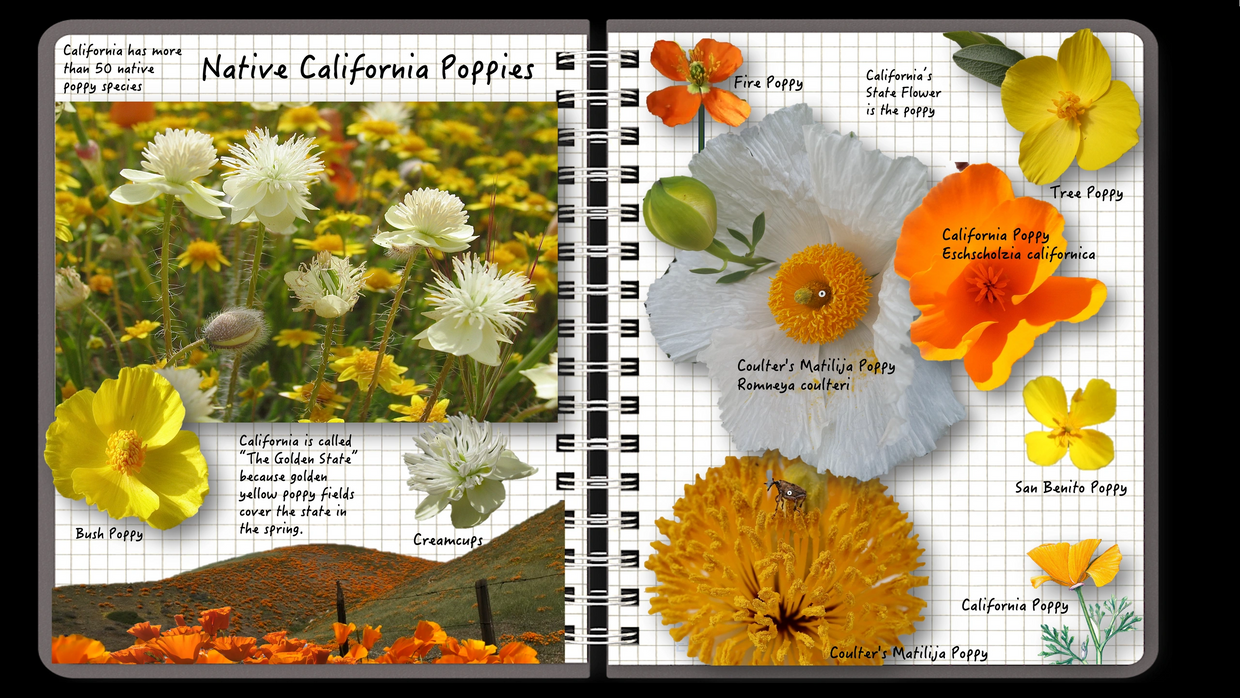

CAlifornia Native Poppies

California, known for its stunning natural landscapes, is home to more than 50 species of native poppy species. These diverse native poppy species found in California captivate with their unique characteristics, ranging from vibrant hues to specialized adaptations. They contribute to the ecological balance, attract pollinators, and serve as a testament to the state's natural heritage. Preserving the habitats of these remarkable poppies ensures the continued existence of their captivating beauty and ecological importance for generations to come.

The California poppy (Eschscholzia californica), once a common sight across the state's landscapes, faces the disheartening reality of disappearing from certain areas. Factors such as habitat loss, urbanization, agricultural practices, and the spread of invasive species have contributed to the decline of this iconic wildflower.

Encroachment of human activities has resulted in the destruction and fragmentation of natural habitats, depriving the California poppy of the suitable conditions it requires to thrive.

Climate change poses a significant threat, as rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns can disrupt the delicate balance necessary for the poppy's germination and growth. Large swaths of land in the Antelope Vally are being covered by massive solar farms, displacing many native flowers.

To preserve the California poppy and prevent its further disappearance, concerted efforts are needed to protect its habitats, promote conservation initiatives, and raise awareness about the importance of preserving this symbol of California's natural heritage.

These diverse native poppy species found in California captivate with their unique characteristics, ranging from vibrant hues to specialized adaptations. They contribute to the ecological balance, attract pollinators, and serve as a testament to the state's natural heritage. Preserving the habitats of these remarkable poppies ensures the continued existence of their captivating beauty and ecological importance for generations to come. Below are a few of the more than 50 native California poppies.

California Poppy (Eschscholzia californica): Undoubtedly the most famous, this iconic poppy species boasts brilliant golden-orange blooms. As California's state flower, it symbolizes the state's natural beauty and resilience.

Matilija Poppy (Romneya coulteri): Known as the "fried egg poppy," it exhibits large, showy white flowers with vibrant yellow centers, resembling fried eggs.

Antelope Valley Poppy (Eschscholzia parishii): Endemic to the Antelope Valley region, it features delicate pale yellow to orange blossoms that create spectacular floral displays.

Island Poppy (Eschscholzia glyptosperma): Native to the Channel Islands, this poppy species charms with its delicate pale yellow to white flowers.

Silver-leaf Poppy (Eomecon chionantha): Found in northern California, it stands out with its silver-hued foliage and graceful white flowers.

Arctic Poppy (Papaver radicatum): Thriving in high-elevation regions, such as the Sierra Nevada, it displays charming yellow or white blooms, often found in alpine meadows.

California Horned Poppy (Glaucium flavum ssp. flavum): Adorning coastal areas, it boasts distinctive yellow flowers adorned with horn-like structures.

Harford's Poppy (Eschscholzia hypecoides): Native to central and southern California, it showcases creamy yellow flowers and finely divided fern-like foliage.

Island Bush Poppy (Dendromecon harfordii): Found on the Channel Islands, it graces the landscape with its vibrant yellow flowers and shrub-like growth.

Bush Poppy (Dendromecon rigida): Endemic to California, this poppy species displays bright yellow flowers and dense, evergreen shrubbery.

Mexican Gold Poppy (Eschscholzia californica ssp. mexicana): A subspecies of the California poppy, it exhibits vibrant yellow to orange blooms and is found in southern California.

Arctic Poppy (Papaver radicatum): Thriving in high-elevation regions, such as the Sierra Nevada, it displays charming yellow or white blooms, often found in alpine meadows.

California Horned Poppy (Glaucium flavum ssp. flavum): Adorning coastal areas, it boasts distinctive yellow flowers adorned with horn-like structures.

Harford's Poppy (Eschscholzia hypecoides): Native to central and southern California, it showcases creamy yellow flowers and finely divided fern-like foliage.

Island Bush Poppy (Dendromecon harfordii): Found on the Channel Islands, it graces the landscape with its vibrant yellow flowers and shrub-like growth.

Bush Poppy (Dendromecon rigida): Endemic to California, this poppy species displays bright yellow flowers and dense, evergreen shrubbery.

Mexican Gold Poppy (Eschscholzia californica ssp. mexicana): A subspecies of the California poppy, it exhibits vibrant yellow to orange blooms and is found in southern California.

Palmer's Poppy (Eschscholzia lemmonii): Native to the coastal regions of California, it features pale yellow to cream-colored blossoms and deeply cut leaves.

Mojave Poppy (Kallstroemia grandiflora): Thriving in the Mojave Desert, it showcases large, showy yellow flowers with orange centers, adding bursts of color to the arid landscape.

Palmer's Poppy (Eschscholzia lemmonii): Native to the coastal regions of California, it features pale yellow to cream-colored blossoms and deeply cut leaves.

Mojave Poppy (Kallstroemia grandiflora): Thriving in the Mojave Desert, it showcases large, showy yellow flowers with orange centers, adding bursts of color to the arid landscape.

superbloom

Nature's Grand Spectacle: The Rare and Enchanting Superblooms of the Southwest

A "superbloom" is a rare and stunning natural phenomenon that occurs when a high proportion of wildflowers blossom at roughly the same time, usually covering landscapes in a vibrant blanket of flowers. This event happens approximately once in a decade in certain arid regions, most notably in various parts of California and the southwestern United States.

The phenomenon is dependent on the perfect alignment of several environmental conditions. For a superbloom to occur, the region must first have been subjected to prolonged periods of drought. This is followed by substantial and well-timed rainfall in the autumn and winter, which helps to soak the hard, dry ground and awaken dormant seeds. Additionally, the area must experience a cold winter but avoid a late-season cold snap that could damage sprouting plants. Finally, the arrival of spring must bring mild temperatures and light winds to protect the delicate blossoms and allow them to flourish.

When these conditions align perfectly, the result is a superbloom, a sea of color that transforms the typically barren landscape into a painter's palette of vibrant hues. During this period, hillsides and valleys are blanketed with vast expanses of flowers in all colors of the rainbow, including orange California poppies, purple lupines, yellow goldfields, and white desert lilies, among others.

The event not only creates a visual spectacle but also leads to an explosion in local insect and bird populations, who feast on the nectar and pollen provided by the flowers. This, in turn, draws in larger predators and contributes to a brief but significant surge in the area's biodiversity.

MAY 2023 - indianBRUSH, colorful Parasites

Indian Paintbrush

Nature's Colorful Parasites: Unraveling the Intriguing Indian Paintbrush

The Indian paintbrush (Castilleja spp.) is a unique and striking group of wildflowers found in North and Central America, known for their vibrant colors and distinctive appearance. However, what makes these flowers even more fascinating is their parasitic relationship with other plants.

Indian paintbrushes are partial or hemiparasites, which means they obtain some of their nutrients through parasitism while also conducting photosynthesis like regular plants. They belong to the family Orobanchaceae and are often found in grasslands, meadows, and open woodlands. They have a unique appearance, with showy, tubular flowers clustered on tall, slender stems and often adorned with colorful bracts that resemble brushstrokes of red, orange, yellow, pink, or purple, hence the common name "paintbrush."

The parasitic relationship of Indian paintbrushes involves tapping into the roots of neighboring plants with their specialized root-like structures called haustoria. These haustoria penetrate the roots of nearby plants and establish connections with their vascular systems, allowing the Indian paintbrushes to extract water, nutrients, and carbohydrates from the host plants. This parasitic relationship allows Indian paintbrushes to thrive in nutrient-poor soils and compete with other plants for limited resources.

The parasitic relationship of Indian paintbrushes with other plants has significant ecological implications. While the host plants may incur some costs from being parasitized, the Indian paintbrushes also contribute to the ecosystem by providing food and habitat for pollinators such as hummingbirds, bees, and butterflies. Additionally, Indian paintbrushes can also influence the composition and structure of plant communities by affecting the growth and survival of their host plants.

APRIL 2023 - plant Galls, Intriguing Formations

Plant Galls

Mysterious and Diverse: Unveiling Nature's Intriguing Formations

Plant galls are abnormal growths that occur on leaves, stems, roots, or flowers of many plants. These intriguing structures are usually induced by various organisms such as insects, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. The interaction between the plant and these gall-inducing organisms results in a unique physiological and biochemical reaction that leads to the development of these often peculiarly-shaped growths.

The gall-inducing organisms manipulate the plant's growth and development mechanisms to create a suitable habitat for themselves. For instance, when a female gall wasp injects her eggs into a leaf or stem, she also introduces chemicals that interfere with the plant's normal growth patterns. The plant cells in the immediate vicinity of the injection site begin to proliferate abnormally and form a gall, which ultimately serves as a protective structure and food source for the developing wasp larvae.

The structure and form of galls can vary greatly depending on the inducing organism and the plant species involved. Galls can be tiny and inconspicuous, or large and visually striking. Some are brightly colored or bear strange shapes, while others may blend seamlessly with the plant. These formations can be round, conical, spiny, or even resemble miniature pineapples or sea urchins.

Despite their often dramatic appearance, most galls do not significantly harm their host plants. However, heavy gall infestations can weaken a plant and make it more susceptible to other stressors, such as disease or drought. In agricultural contexts, certain types of galls can cause significant crop damage and are therefore of economic importance.

march 2023 - Puccinia monoica,Parasitic Tango

The Fungus & the Flower

The Parasitic Tango: Unraveling the Complex Relationship Between Puccinia Monoica and the California

Puccinia monoica is a species of rust fungus that is known to have a parasitic relationship with Boechera retrofracta, a species of wild rock cress, also known as ”California Rock Cress." Boechera retrofracta is a perennial flowering plant that belongs to the Brassicaceae family and is endemic to the high elevation regions of the San Gabriel Mountains in California.

Puccinia monoica infects Boechera retrofracta as a rust disease, causing visible symptoms on the leaves and stems of the plant. The fungus sterilizes the rock cress by affecting its reproductive structures, preventing the plant from producing viable seeds. The fungus forms characteristic pustules or spore-producing structures on the surface of the plant, which release spores that can spread to other plants, facilitating the fungus's life cycle. The infection by Puccinia monoica can cause damage to the foliage of Boechera retrofracta, potentially impacting the plant's growth and reproductive success.

The relationship between Puccinia monoica and Boechera retrofracta is considered parasitic, as the rust fungus derives nutrients from the host plant and causes harm to its tissues. However, the exact impact of the rust infection on the fitness and survival of Boecheraretrofracta is still not fully understood and may vary depending on environmental conditions and other factors. Some studies suggest that the interaction between Puccinia monoica and Boechera retrofracta may be a co-evolutionary arms race, with the plant evolving mechanisms to defend against the rust infection, and the rust fungus evolving strategies to overcome the plant's defenses.

FEBRUARY 2023 - Nudibranchs,toxic sea slugs

SEA SLUGS- Nudibranchs

Unveiling the Vibrant World of Nudibranchs: Nature's Colorful, Toxic Sea Slugs

Nudibranchs, often referred to as "sea slugs," are a diverse group of soft-bodied, marine gastropod mollusks known for their vibrant and often striking colors. The term "nudibranch" is derived from the Latin "nudus," meaning naked, and the Greek "brankhia," referring to gills. This name reflects their distinctive anatomy where their gills are exposed on their dorsal surfaces, rather than enclosed in a shell like many other mollusks.

There are over 3,000 known species of nudibranchs, and they can be found in oceans all around the world, from the shallows to the deep sea. They vary greatly in size, from a few millimeters to over a foot long, and their appearances are just as diverse. This variety is so extensive that some species have evolved to mimic other marine creatures or even their surroundings as a form of camouflage or as a deterrent to predators.

Interestingly, the brilliant colors of many nudibranchs are not just for show. They serve as a warning to potential predators that the nudibranchs are toxic or distasteful. Some nudibranchs are capable of ingesting toxic substances from their prey, such as sponges or jellyfish, and then storing those toxins in their own tissues. When a predator tries to eat a nudibranch, it gets a mouthful of the toxins and quickly learns to avoid them in the future.

Nudibranchs have a short lifespan, typically living for only a few weeks to a year. Despite their short lives, nudibranchs play a crucial role in the ecosystem. Their feeding habits help control populations of other marine invertebrates, and their vibrant colors provide a stunning spectacle for divers and marine biologists alike. Their ability to accumulate toxins from their food sources is also of interest to scientists studying chemical defenses in marine organisms.

JANUARY 2023 - Sequoias, Titans of the Natural World

Sequoias

The Majestic Sequoias: Titans of the Natural World

Sequoias are among the most awe-inspiring and oldest living entities on Earth. These stately sentinels of nature, specifically the Giant Sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) and the Coastal Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), hold records for size and longevity, standing as a testament to the resiliency and magnificence of the natural world.

Giant sequoias, native to the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, are known for their immense size. They are the most massive trees in the world by volume. The largest of these, the General Sherman tree, stands approximately 275 feet tall, boasts a circumference of over 100 feet at its base, and is estimated to be over 2,000 years old.

Sequoias possess a distinct, thick, spongy bark that is cinnamon-hued, giving them their reddish appearance. This bark is also high in tannins, which makes these trees remarkably resistant to diseases, insects, and even fire, contributing to their long lifespans. Some sequoias have been known to live for over 3,000 years, weathering the ages with steadfast endurance.

Beyond their size and longevity, sequoias are an integral part of their ecosystems. Their enormous canopies regulate temperature and moisture levels, creating unique microhabitats for various flora and fauna. Additionally, their massive trunks and extensive root systems play a significant role in maintaining soil stability.

However, despite their impressive resilience, sequoias face considerable threats from human activities, particularly logging and climate change. Logging activities have significantly reduced the sequoia's natural range, and the changing climate poses unprecedented challenges to their survival.